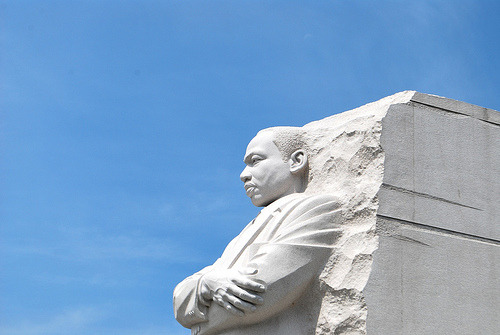

statue of MLK

statue of MLK

Using Martin Luther King, Jr. Day to Rewrite Anti-Racist Mythology

By Muna Mire

I once got into an argument with two white men over race on the internet. That’s not the beginning of a joke, it’s just a shitty thing that happened to me. I’ve since learned my lesson about how “social justice” is deployed online, but at the time it seemed important to engage these two white men in dialogue around their problematic statements.

The argument was about welfare: one of the men initially disagreed with me that perceptions around social assistance — who receives it, what kind of people they are — are heavily racialized even while he himself was deploying raced assumptions about laziness, work ethic, greed, etc.

The other man stepped in to defend his friend.

I really just wanted to give a primer to both men — I saw them every once in a while in my social life — on the historical contexts of the racist stereotype such as the Reagan welfare queen, thinking that if I armed them with the information, they would take my side — me being a Black woman with lived experience. Plus, it seemed obvious to me.

That’s not how the argument ended.

I’ve since reconciled with the initial friend, but I never made peace with the friend who jumped into defend him. In the middle of a difficult conversation about race, and one in which we were not equals, he threw a Martin Luther King Jr. quote in my face to shut me up about racism. He told me that talking about race is divisive and that King believed that we should not judge a man by the colour of his skin. I told him that’s cool (it wasn’t), but white supremacy is a political ontology that structures the world’s semantics and King absolutely believed we should talk about it.

This story is not at all unusual. In fact, I tell the anecdote as a way to relate the fact that how we talk about King today is no longer tethered to reality or history. King is a myth. He is a symbol of a movement and as Melissa Harris-Perry claims, a collective effort on our part. This means that we have all imagined and reimagined, created and recreated, inscribed and reinscribed his legacy with our own normative set of values — deploying King how and when it suits our purposes.

Often, this has very little to do with the substance of King’s political career and is in direct opposition to it. King is not unlike other freedom fighters that have changed over the course of history and have been adopted by history and popular culture, hailed by the governments they once fought ardently against as heroes because of it.

With the recent passing of Nelson Mandela for example, the world saw the hypocrisy of leaders like British Prime Minister David Cameron and Stephen Harper who praised the man they once organized against as young pro-apartheid university students. It’s clear why: if the history of struggle were not sanitized, if the men and women that have become symbols of resisting state oppression were not adopted by the state, the state itself would be cast into moral suspicion.

Aside from absolving the state of its guilt around past transgressions, the mythologies generated around these figures act to disrupt the progress and gains of social movements. MLK has been canonized and commercialized all at once — it feels like his children live in court suing other people over their father’s estate, rather than continuing his work.

How many classroom posters depict stills from the “I Have A Dream” speech? How many classrooms name white supremacy for what it is? MLK is a household name — and as horrible as it is, there’s money and a lot of feel-good rhetoric in that. It was the spirit of “racial reconciliation” that Mandela was praised for and not his armed resistance, it’s King’s dream that his children “not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character” — an adage constantly deployed by white people who feel judged — but never his message of radical economic justice that is talked about.

Similarly, we never touch upon the failures and shortcomings of King because we’re too busy feeling good about ourselves. The man changed the course of history, he was brilliant beyond measure, but he was flawed in many, many ways.

He was criticized by his female peers often, and the movement he came to symbolize treated the women that were a part of it poorly at best. If we don’t honestly talk about these things, if we don’t honestly talk about the fact that there was an entire movement behind King, that Rosa Parks was a trained organizer, not just a woman who refused to give up her seat on whim — we can’t learn from the past.

Movements don’t happen because of charismatic individuals, movements happen because people organize, raise consciousness and treat each other and the oppressor humanely. By making it seem as though the state, or white people at large, responded to the civil rights movement out of the goodness of their hearts, or because of a spectacle put on by a few charismatic individuals, you erase the years and years of organizing work that people like Bayard Rustin, Ella Baker and Fannie Lou Hamer put in. And that not only is disrespectful to their legacies it means we won’t have learned from the past at all.

The famous photo of Martin Luther King being arrested is symbolic of the historical erasure and co-opting of King’s legacy. If you look at the picture, you see Dr. King getting arrested by white police, but behind him, barely visible, are two women. Melissa Harris-Perry points out the significance of the image in this video clip: If you don’t look closely at the picture though, you would miss them entirely.

This MLK day, I think we should all be looking at the picture a little more closely.

Muna Mire is an organizer, writer and a Black girl from the future. A recent University of Toronto grad, she is a member of the editorial board of {Young}ist, a young people-powered media start up. You can find her freelance work at Bitch, Huffington Post, The Feminist Wire, and elsewhere. Her interests include progressive politics, movement building, postcolonial literature, feminisms and speaking back to The Man.

Muna Mire

Organizer, Writer, Black girl from the future.

Catch up with me @Muna_Mire.