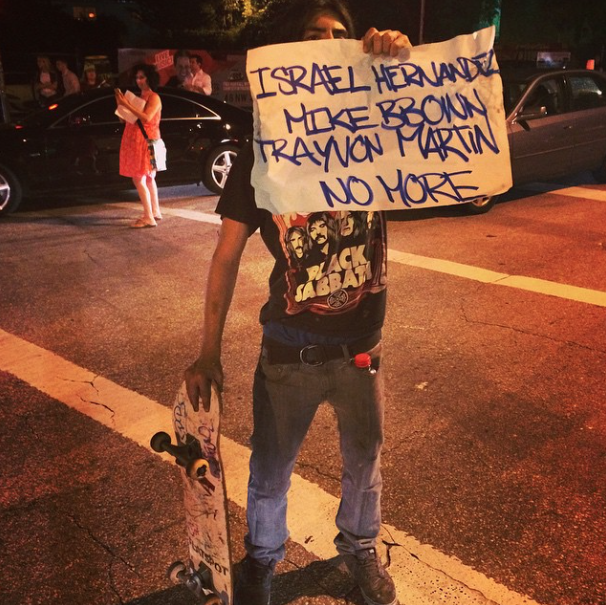

The opening of Art Basel in Miami (Left) and a photo from the Ferguson protests (Right).

The opening of Art Basel in Miami (Left) and a photo from the Ferguson protests (Right).

The Silence of Art Basel — Police Violence, National Unrest and Other Stories

Editor Hira Mahmood attends Miami's Art Basel, and is faced with a number of questions pertaining to the roles of revolution and art.

By Hira Mahmood

I don’t call myself an artist – but that doesn’t mean I’m not intrigued by the artist’s world. From the position of a consumer and patron, I’m invested in exploring the false separation of art and the socio-political world. My experience mostly comprises working on widespread campaigns, such as anti-budget cuts and eradication of police programs housed on our public university campus. In Atlanta, GA, my involvement in art is a matter of engaging in local community art projects with talented peers who are into ephemeral media, digital gallery spaces, and capturing the generation of the #endlessscroll. Atlanta is a sprawl, so finding pockets of activists who share similar feelings on artistic processes, issues, and utilizing underrepresented media forms makes me feel hopeful about building long lasting projects in the city.

In 2013, I found myself attending Art Basel with some artist friends to expose myself to what the art market and institutions look like on a grand scale. This year, I went to Basel with hopes of finding signs of how contemporary art reflects our current socio-political positions and where we can find pockets of resistance devoid of exorbitant and inflated art.

ART AND POLITICAL POTENTIALS

In its 13th year, Art Basel Miami is a showcase of the global art market where gallerists, collectors, and the incredibly wealthy flock to Miami Beach for the latest trends and, of course, the Florida sun. From December 4th to 7th, Miami swells as private collections unveil new showings, overwhelmingly glamorous parties rage, and, one hopes, ideas cross-pollinate. The art climate in Miami is a matter of intricately woven layers: from Basel itself to the Design District, galleries on every corner of the city, and the street art that covers Wynwood and graffiti writers from all over the world, there’s too much to take in.

Miami’s glamor was particularly hard for me to swallow as images of revolt were relayed across the country. Ferguson burned, and across the U.S., thousands of demonstrators blockaded highways and occupied public spaces. Generational gaps between young people and civil rights leaders turned into rifts reflected in disagreements on tactics, as evident in previous generations’ willingness to collaborate with the police and other forces of order.

Let’s not kid ourselves – expecting Art Basel to bring political struggle and analysis to the forefront is wishful thinking indeed. Even if our hopes for nascent art and inspiration are not met, we can count on the art market to bring out the one percent. At the same time, though, many artist collectives continue to push back against artistic hierarchies.

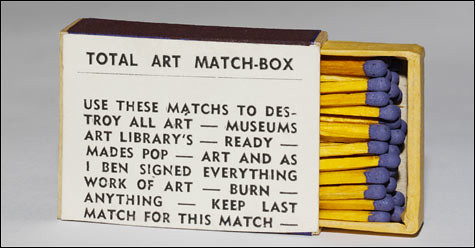

In the 1950s and 60s, the art movement Fluxus, comprised of artists like George Maciunas, Joseph Beuys, and Yoko Ono, took an anti-commercial stance and subverted so-called high art. The Guerilla Girls formed in the 1980s and used subversive tactics to promote women in art. Art collective Claire Fontaine began in France in 2004 as ‘an ongoing interrogation of the political impotence and the crisis of singularity that seem to define contemporary art today,’ primarily using neon, video, text, and sculpture and aiming to inject collective meaning. At the end of 2014 in Miami, I was left wondering: given that art is an instrument for the opening of controversial conversations and contentious spaces, are there ruptures to be found in even the most suffocating spaces?

Guerrilla Girls propaganda, 1989.

Guerrilla Girls propaganda, 1989.

WHO REALLY MAKES MIAMI AN ARTIST’S CITY?

The art world is a violent world. It forecloses opportunities to poor people, people of color, and Black artists in particular. It is a world that profits from the unseen and unacknowledged influence and power of labor via appropriation and extraction of oppressed peoples. Art Basel in congruence with police murdering Black and Brown Miami residents in the streets is part of this systemic violence.

Other spaces have addressed appropriation of oppressed peoples’ intellectual labor as well. A collective of unaffiliated Black women and women of color published a manifesto titled #ThisTweetCalledMyBack, rejecting the plagiarism and appropriation of their intellectual-digital labor. Their astute analysis of the academic and nonprofit industrial complexes allows us to draw parallels to art institutions as well.

The white and wealthy control the funding streams and art foundation boards. They colonize, mine, and extract cultural artifacts constructed by the colonized, then sell concepts and subjects as their own, caging precious relics in museums and galleries as a neo-colonial project. This is the world that paved the way for international art fair events like Art Basel.

So, who really makes Miami an artist’s city?

Here we must call upon the name of 21-year-old graffiti writer Delbert Rodriguez Gutierrez, a.k.a. ‘Demz,’ who was run over by a police officer in an unmarked vehicle while allegedly painting on a wall in the Wynwood neighborhood. We must call upon Israel “Reefa” Hernandez, another young street artist who was tasered to death by a police officer in Miami in August 2013. It is these young people and their friends that threaten the status quo and deface the sanctity of the art world. These are the culture-creators and, simultaneously, accomplices for directly challenging our notions of public versus private spaces, private property, and acceptable forms of artistic expression.

The same night that 21-year-old Demz was killed, protesters shut down the Wynwood arts neighborhood, just a few blocks away, in solidarity with Ferguson. Organizations reorienting Black and Brown youth such as #BlackLivesMatter and the Dream Defenders stood in the middle of I-95. From beautifying and vandalizing walls to protesting ‘business as usual,’ we must align the work of disrupting the flow of capital with the work of artists like Demz and Reefa who continue to be targets of state violence.

December 5 highway blockade, Miami.

December 5 highway blockade, Miami.

Both the legal and illegal walls of Wynwood, an up-and-coming arts district in Miami, feature art from graffiti and street artists. As gentrification decimates yet another neighborhood, Wynwood feels more like an artscrawl and less like what it once was – the home of primarily Cuban and Haitian working-class families, then a popular fashion and garment district in the 1970s and 1980s, and now, the burgeoning arts neighborhood.

Ben Vautier’s _Total Art Match Box_ is part of “Multiple Strategies: Beuys, Maciunas, Fluxus” at the Busch-Reisinger Museum.

Ben Vautier’s _Total Art Match Box_ is part of “Multiple Strategies: Beuys, Maciunas, Fluxus” at the Busch-Reisinger Museum.

BASEL AND #BLACKLIVESMATTER TAKE ON DIGITAL SPACES

Art Basel isn’t just a showing of typical art – it’s also composed of a list of discussions and salons. One particularly frustrating talk that my peers and I attended was titled “Instagram as Artistic Medium.” The five-person panel included Klaus Biesenbach, Simon de Pury, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Instagram CEO and co-founder Kevin Systrom, artist Amalia Ulman, and Bettina Korek as moderator.

Amalia Ulman spoke first, explaining her work’s examination of “referential treatment.’ Nodding to Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, Ulman addressed the imagination of the ‘me’ and the presence of discourse alongside the image. Reading aloud, calmly and disconnectedly, from her iPhone, Ulman described her work as an exploration of different notions of femininity, and as blurring the lines of the artist and the object of study. Ulman concluded her performative lecture with a disconcerting question: “How do we consume images, and how do they consume us?”

CEO Kevin Systrom “answered” with a piece that was more or less a pitch of Instagram’s mission. Instagram, according to Systorm, exists to ‘capture and share the world’s moments’ in three ways: 1. Inspire creativity, 2. Community first, 3. Simplicity. Simon de Pury exclaimed, “Every user of Instagram is basically an artist! And it is absolutely marvelous.”

The rest of the panelists were unsure of how to follow Ulman’s subversive, conceptual discussion of self-formation and digital spaces. Ulman was the only panelist to mention capitalism; Ulman was the only panelist to mention power relations; Ulman was the only panelist situating her artistic process within the advents of late capitalism. Again, should I be surprised? What did I expect from a talk at Art Basel in which the Q&A portion repeatedly acknowledges the white male audience member rather than the feverish waves of my and my friends’ colored hands? What’s up with the reliability with which crucial conversations quickly flatten and dissolve? And when these conversations do dissolve, what do we do with the residue?

But what about the utilization of digital spaces for protest? Social media avenues in the midst of anti-Black violence found a stronghold particularly in the voices of Black youth, Black women, queer people of color, and women of color. As #BlackLivesMatter trends online, hundreds of thousands are mobilizing in the streets, moving beyond identity markers based on organizations and political affiliations and instead identifying as a movement “affirming the lives of Black queer and trans* folks, disabled folks, Black-undocumented folks, folks with records, women and all Black lives along the gender spectrum. It centers those that have been marginalized within Black liberation movements. It is a tactic to (re)build the Black liberation movement.”

Even though the #BlackLivesMatter began as a hashtag, they conclude, “We have put our sweat, equity, and love for Black people into creating a political project – taking the hashtag off of social media and into the streets.”

In case anybody is still wondering if #BlackLivesMatter is a radical movement – if it can leverage its own potential to move beyond the liberal reforms demanded by small groups – virality might be a good sign of where we are headed. Vines, tweets and Instagram videos have popularized words we couldn’t have even imagined going viral during Occupy Wall Street: Words like “de-arrest” and playful iterations of “police abolition” like “no cop zone.” Even if the young leadership being held up by liberal media outlets have yet to demand a world without police, conversations in disparate corners of art, political and digital spaces seem to be.

One group spearheading Black and Brown youth organizing by utilizing social media is the The Dream Defenders. Not only are the Dream Defenders known for bringing out masses of young people or for their contentious actions against police (like shutting down the Sanford Police headquarters); the Dream Defenders also have an unparallelled branding and logo design that helps capture the spirit and vitality of the civil rights movement without being anchored down by the legacy of civil rights.

Sandra Khalifa is the former Communications Director and Graphic Designer for the Dream Defenders. In an interview with Waging Nonviolence, Khalifa describes how her artistic expression expanded through the #hashtag. What struck me the most was the #VisitFL campaign in which the Dream Defenders made advertisements for Florida, pushing back against Florida’s sanguine reputation and instead focused on the violence and incarceration people of color face in the sunshine state. Khalifa explains, “I got to use my creativity freely and just come up with things I thought were moving or beautiful to explain complex, heavy issues and policies.”

Sandra Khalifa’s work for #VisitFL campaign.

Sandra Khalifa’s work for #VisitFL campaign.

SO WHAT?

Perhaps the most striking piece of artwork I saw in Miami in the Rubell Family Collection is titled Guernika, by Lucy Dodd (b. 1981). Born 100 years to the day after Picasso, Dodd engages in her own an interpretation of Picasso’s Guernica as she adopts fleshy colors and explosive texture. The towering work is made of earth-drawn materials such as Rio Tinto water, chamomile and pomegranate from Segura de Leon, and Miami rainwater and lavender oil.

I close with Lucy Dodd’s Guernika for a few reasons. For those who aren’t familiar, Picasso’s Guernica depicts the bombing of Guernica, a village in the Basque Country in Spain, in 1937 by German forces. Showcasing the torment of innocent civilians, the painting stands as a profoundly anti-war work of art that has become a cultural artifact capturing human suffering at the hands of war.

Lucy Dodd, Guernika, 2014.

Lucy Dodd, Guernika, 2014.

Fast forward to 2003 when, ‘in an act with extraordinary historical resonance,’ Secretary of State Colin Powell delivered an address to the United Nations making a case for war against Iraq. The tapestry hung behind Powell during his speech was a replica of Guernica. Coincidentally, it was decided the Guernica replica be covered with a blue drape. It would not be enough to say that the painting delegitimizes Powell’s case for war against Iraq – what needs to be recognized here is that if art cannot be a revolutionary act in itself, it is still the revolution of ideas. Yes, something changes when we see Guernica moving from a museum wall onto a backdrop ornament making a case for war. Yes, something changes when you look at graffiti on the street versus a graffiti piece actually cut out of the wall and placed in a gallery space.

Banksy, Red Hook Balloon, 2013. Keszler Gallery.

Banksy, Red Hook Balloon, 2013. Keszler Gallery.

Of course, Art Basel as an art market event is not going to address the political struggles that Black, Brown, immigrant, queer, and trans* bodies face in this country – at least not subversively. Basel may appropriate our bodies ‘for art’s sake.’ But does that mean we throw art – the artists, speakers, objects, performances, galleries, the entire milieu – to the wind, and instead look for other means of political expressions and forms of agitation? It would be tempting to say yes, if an art event like Basel was the only experience I’d ever had. However, since my aim is the liberation of all oppressed peoples, artists like Ulman, Khalifa, artists from Dignidad Rebelde, and even the artistic shifts that we are currently participating in that we have no name for yet show unparalleled possibilities in actually changing how art reflects our social world.

Hira Mahmood

another peon with an english degree

Catch up with me @HiraMahmood5.