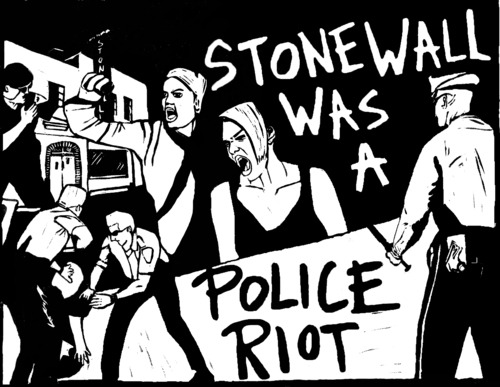

illustration of people yelling at police with the words 'Stonewall was a police riot'

illustration of people yelling at police with the words 'Stonewall was a police riot'

Re-Queering Pride

How can we get back to the radical roots of our LGBTQ movement?

By Ngoc Loan Tran

The history of Pride in America

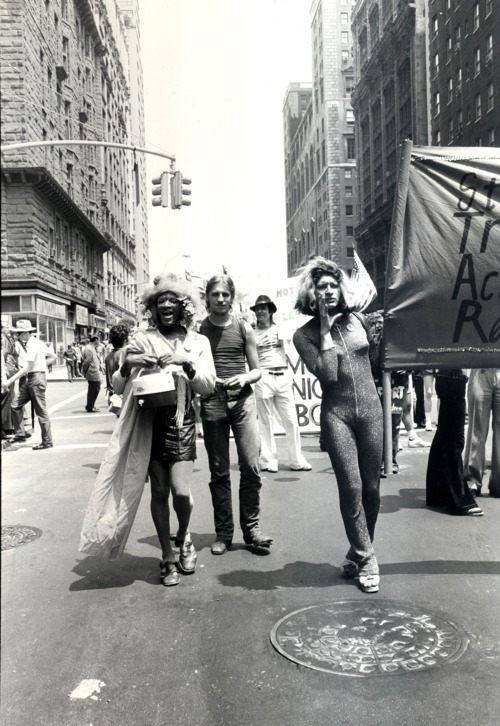

June was Pride month in the United States. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender folks from coast to coast celebrated the history of queer resistance led by drag queens, poor and homeless queer youth, and trans* women of color like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson… oh what? Word? That’s not what you thought Pride was? Well, maybe that’s because it isn’t what Pride looks like these days.

For some members of the LGBT community, June arrives in an explosion of glitter and rainbows, complete with crowds of sweaty half naked gay men drinking Absolut Vodka and signing up for Wells Fargo savings accounts. But for others, June comes as a reminder that while Pride month is about LGBT folks proclaiming our existence, many of us – queer and trans*, disabled, fat, migrant, poor – have to try a little harder to be recognized, to have our histories remembered and our struggles made visible.

The events of June 28th, 1969 wrote queer and trans* folks into history permanently. While the Stonewall Riots that began on that night were not the first time the LGBT community retaliated against anti-queer and trans* violence (see: the Compton Cafeteria riot of August 1966), the Riots are often regarded as the spark that began the ‘gay liberation movement.’ The Riots were an intentional disruption of the routine police raids that took place at the popular Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village.

The Riots served as a catalyst for queer and trans* folks, particularly those living in New York City, to come together and work towards building a community invested in actively resisting targeted violence. A year after Stonewall, cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York City held their first ‘Gay Pride’ marches to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the Riots that started it all.

Reflecting on Pride today

Today, Pride is no longer intentional in the way it is politicized. Pride events are divorced from their historical legacy, and they do not carry the same weight they once did. In the interest of transparency, I want to make it clear that I have only been to two Pride events: one in Charlotte, North Carolina and the other in Manhattan. But between these two cities and between these two Prides, I have an understanding of the general landscape of what Pride looks like today: sponsorships from major banks and corporations like JP Morgan Chase and Target, partnerships with major alcohol manufacturers like Absolut, and a plethora of non-profits wishing they had prettier branded merchandise to lure the gays (and their wallets) in with.

Pride events across America have been transformed into optimal environments for cultivating collective amnesia. We forget that queer and trans* people are still facing dire poverty and homelessness. As a result of joblessness, many of our folks struggle with substance abuse as a way to cope and fulfill needs we cannot satisfy elsewhere. Queer and trans* people of colour in our community experience heightened levels of violence and harassment through profiling, incarceration, detention and deportation. And this comes in addition to the violence inflicted upon our bodies for being anything other than what the heteronormative standard dictates.

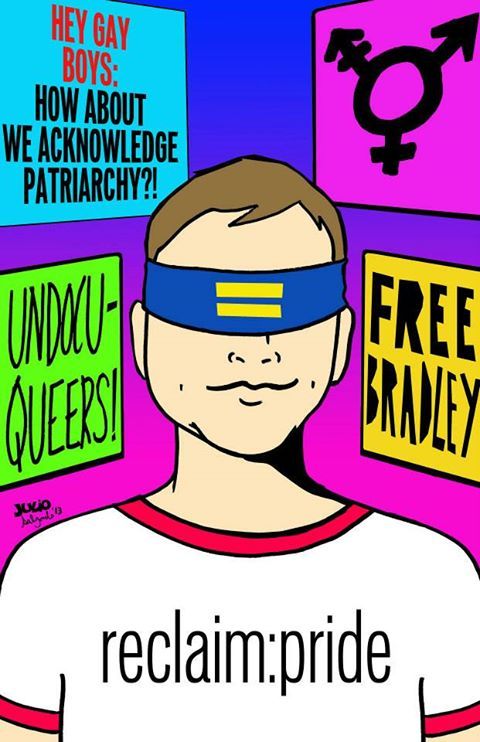

As queer and trans* people, we are still facing injustice for simply existing as we are. As people with multiple oppressed identities, our struggles may not always center anti-queer and anti-trans* injustice. And yet, we cannot separate ourselves into pieces or compartmentalize the multiplicity of our deeply interconnected struggles. My being a person of color, an immigrant and disabled brings traumas and challenges that need to be recognized as a part of the queer and trans* struggle. As Audre Lorde famously said, “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

In forgetting that our struggles exist beyond the micro-aggressions of anti-queer and anti-trans* slurs, not only do we minimize our responsibility to stay observant and critical, we actively endorse spaces like Pride that contribute to the violence inflicted on our people. And while it’s not our fault that governments still treat us with inequity or that corporations seek to exploit us, we cannot remain silent as Pride becomes about shallow partnerships between banks and alcohol companies that contribute to our oppression. It’s the major banks that are the ones foreclosing on our queer and trans* family. It’s the major alcohol corporations that capitalize on the substance abuse in our community.

Corporatizing Pride and desirability

Pride celebrations today contradict the vision planted 44 years ago by reinforcing a hierarchy of desirability that queer and trans* people struggle with on numerous fronts. In many ways, this hierarchy is encouraged and upheld by the corporatization of Pride.

Pride is most comfortable for gay folks who experience their queerness in the context of being white, skinny, able-bodied, and financially secure. These are the bodies that are seen as desirable within the context of Pride and their experiences are centered, often at the expense of the humanity of others. This sort of comfort is evident in the ways Pride events can still develop relationships with banks and corporations while ignoring the ways these very institutions do our larger community harm. Internalizing these relationships as a reflection of the “progress” we have made doesn’t indicate progress at all; it means the internalization of the oppression we face. It means that our desirability is still being defined by those with power over us.

The Stonewall Riots were led by members of our community who were considered undesirable by other lesbian and gay folks because of their skin color, their means of survival, their gender, their class status or even their politics of radical change. Outside of the queer community, those who led the Riots were considered undesirable by the government and larger society as well. Their legacy planted a vision of a future where we would create our own standards of desirability that actively undermine oppressive systems and structures.

On some level, I think we know that there is work left to do. We know that Pride today is not reflective of our history, and does not center the experiences of those who live at the intersections of oppression and are seen as “undesirable”. Rather, the inaccessibility of most Pride spaces means many of us do not see ourselves fully reflected or represented. I often find myself being forced to choose between parts of myself, different aspects of my identity, as I navigate the urge to celebrate while wanting to remain critical and being discouraged from doing so.

Pride does not foster a sense of community. We see that evidenced in the way that intentional, politicized spaces like Black Gay Pride, Dyke Marches, and Trans* Days of Action must be created even within Pride. These kinds of internal Pride spaces serve as an alternative for folks like me who have felt alienated and foreign in mainstream Pride spaces from Charlotte to Manhattan.

Don’t get me wrong, I believe in celebrating. I believe that we queers should celebrate ourselves as we live through the daily horrors. There is celebration in liberation, and in this process of revolution. But, I also believe that being critical while celebrating is possible and necessary. I believe in our collective responsibility to one another to deal with oppression in all of the ways it manifests. We need to have tough conversations about how Pride is often most comfortable for the people in our community that possess profound privilege alongside their queerness.

A tough conversation

I don’t want us to forget that trans* women of color are still seen as disposable, or that rural queer and trans* youth still contend with deadly silent, isolating environments. I don’t want us to forget that queer and trans* people of color are still being profiled and harassed, and that we are still losing people as a community.

I don’t want us to forget that heterosexism needs us to believe that we have succeeded.

I do not want us to forget that liberation does not mean we become the kind of queer that heterosexuals can call friend while ignoring their immense power over us; I do not want us to forget that we still need a world created in our queer image.

I want to recognize that we won’t all of a sudden be delivered to a Pride that is imbued with a totally beautiful, radical, and anti-oppressive magic. We must deliver ourselves. But I am a queer with limitless hope, and I believe that rooted in the magic of our collective resistance is the possibility of making Pride queer again.

I want us to remember history and hold the sacrifices of our queer and trans* ancestors in our bodies. I want us to be present in the now as it unfolds and reveals that after a June drunk with corporate excess, heavy and heartbreaking work remains.

I want us to recognize that there is celebration in queerness and there is no such thing as the wrong time to talk about ourselves. I want us to remember ourselves as complex, multi-layered people who have more power than we are led to believe. And when I talk about our power, I do so in a way that honors the vision of our ancestors who called for liberation, justice and freedom over heterosexist privilege. I’m talking about a power that is responsible, that does not forget our roots or ignore our potential to be transformative and intentional in all we do.

A call to action

The urgency of a day that is better than today is still real for so many of us. And if Pride events across America and worldwide want to advertise themselves as spaces for community, then I need us to make Pride queer again. I need us to be real with one another and with ourselves. I need us to dance and sing in the streets with conviction about our struggles with faith in the fact that we will win. I need us to make out, make love, hook up and be tender with each other with justice in mind. Because that is who we are, and that is the legacy we come from.

I refuse to believe that one month out of the year fixes it all, that Pride parades and street festivals are proof that we have made it. Heterosexism and other oppression does not pause for breath when corporations hijack queerness for profit. They pretend to care about our lives: they don’t.

I refuse to believe that this is it. Not when time and time again, our experiences of limitless queerness have shown us otherwise. I believe that we can carve out a place for ourselves in this world where we don’t hide behind the struggles we still face. Pride can be a part of our revolution and movements.

I write this in honor of the queer and trans* folks who lit the torch, setting my belly on fire and pushing me to stay critical. I write this in honor of queer and trans* folks who are still out there doing the work of liberation. I write this in honor of those queer and trans* folks for whom Pride comes like a gift from heaven. I write this in honor of all the different ways queers are making it in this world, and I write this with hope for all the ways we can do better by each other and ourselves.

You can follow Loan on Twitter @NTranLoan.