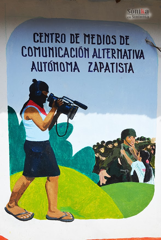

Photo of a wall with a mural with two faces and EZLN slogans

Photo of a wall with a mural with two faces and EZLN slogans

Reimagining Freedom: One Student’s Take on the Escuelita

By Molly Stuart

Laughter rolls out of the women around me and mixes with the smoke of the wood fire. The thread was all tangled again because I just dropped part of the loom on the dirt floor. The mother of the house, her daughter, and my guardian find it all very funny. My cheeks turn as red as the bag we are weaving. They hand me a tortilla fresh off the fire, perhaps hoping that some naturally grown corn would make me a little more nimble. Soon I feel the mother’s hands on my own, tracing the pathway for the next row of stitches, patient but firm. These hands are constructing autonomy daily. And the Escuelita has given us the chance to learn from them.

At the turn of the new year and the 20th anniversary of the Zapatista Uprising, about 5,000 students descended on Chiapas, Mexico, to attend rounds 2 and 3 of the Zapatista Escuelita (Little School). We came to learn how the Zapatistas are resisting neoliberal domination and building autonomy – both as a lived practice and long-term political vision. We were not schooled by a centralized political leadership but rather given the chance to experience the collective work, the leadership structures, and the social relations of the base communities. The fruit of this educational project will continue to appear as the students of the Escuelita scatter around the world to plant new forms of autonomy “from below and to the left.”

To begin our weeklong course on “Freedom According to the Zapatistas,” we left in caravans to the 5 Caracoles, home of the Juntas de Buen Gobierno (Good Government Council), and were later distributed throughout 1,000+ communities within the Zapatista Autonomous Rebel Municipalities. The organizational capacity to transport, feed, house, and welcome so many students was a demonstration of the Zapatista’s current strength, despite the many forms of counter-insurgency that the Mal Gobierno (Mexico’s treasonous government) still pursues.

In this sense, the Escuelita is certainly a direct form a resistance. In it, the Zapatistas reject corporate media that propagates lies about movement dormancy or internal conflict, and instead communicate with allies from around the world who come to listen, learn, and disseminate. The materials offered to us, four books and two DVDs, were made by community-run media projects. And the form of education is in direct opposition to that of government schools and defy the logic of individualism and competition that dominant culture tries to teach us.

I landed in the caravan headed to Caracol La Garrucha –“Resistance Toward a New Dawn.” We were received by hundreds of Zapatistas, who were clapping and yelling out cheers for our safe arrival, for their heroes and martyrs, and for the beliefs that give them reason to be. We were greeted by our guardianas and guardianes who remained by our side as tutors, translators, and companions for the entirety of the Escuelita. They offered us delicious tostadas and beans served out of a pot that could have fit two people my size. And we danced, our feet resisting the thick pull of the mud and our temporary community resisting the time and space of capitalism. Because as Subcomandante Marcos says, “Rebellion, friends and enemies, is something that has to be celebrated, every day and at every hour. Because rebellion is also a celebration.”

On the first day of class we listened to over thirty teachers talk about their autonomous education, healthcare, justice, government, and economy. They explained how autonomy informs, and is informed by, their collective work, access to natural resources, relationships of solidarity, and cultural practices. A common line was, “We didn’t have a master plan, we weren’t following a rulebook, but we tried this and we think it’s working.”

The next day I arrived in a community three hours from La Garrucha. The whole town lined up on the road to greet me and the other students (two from Colombia and one from Quintana Roo). They wore their paliacates (bandanas) over their faces for security (whenever cameras are present) and as a symbolic act – they cover their faces so they can finally be seen. We were then led to the homes of the families that agreed to host us.

Over dinner, I asked the mother of the house what she considers the biggest change since the community became Zapatistas. She replied, “If there is abuse, the women rise up to stop it. They can and they do. We are also proud of our work now, in our collectives and in the good government.” This type of change was enabled in part by the Revolutionary Women’s Laws, which banned alcohol and drugs in all rebel communities, among other things. If the law is broken, the guilty community member must do extra collective work.

In the morning, we watched a group on horseback round up a herd of cattle to vaccinate them. These folks, forming part of the larger collective, told us that their herd has grown significantly over the last few years. The next day we saw the other collective business that garners cash income for the community – chili cultivation. My guardian explained that the money they make from this work, they are able to purchase materials for their autonomous schools and clinics.

Most of the time I spent with community members was not doing collective work but tending to the details of subsistence living. For my host family, this meant waking up before dawn to make tortillas, chop wood, weave clothes, take care of their animals, and prepare meals of beans, squash, rice, bananas, and sweet coffee. All the while, we listened to radio insurgente – the rebel radio that broadcasts discussion, news updates, and traditional music.

By noon time we were always ready for a break, so the whole town congregated in the yard between the chapel and the schoolhouse to help us study. The other students and I read from our textbooks and asked questions to our guardians, who would then consult with others and bring us back an answer. It was not a formal class that required many teachers, but the majority of the town was there to partake. To sit, converse, and exist in community.

Throughout the week, as our guardians translated between Spanish and the indigenous languages of our host families, we observed whole communities translating the principles of Zapatismo into lived realities. Students from every caracol reported back that despite the differences in geography, language, and history between various Zapatista communities, they are all committed to a set of seven principles:

-

Serve and don’t self-serve

-

Represent and don’t supplant

-

Construct and don’t destroy

-

Propose and don’t impose

-

Convince and don’t conquer

-

Go below and not above

-

Lead by obeying

With the Mexican government and corporate associates as a counter-model, Zapatista leaders on all levels are not paid for their work. Instead, their communities support them with the resources they need to survive. A local authority explained that the autonomous governments primarily serve to “coordinate between communities, maintain Zapatista territory and promote collective work, and facilitate projects with solidarity groups.” They do not hold any special power over the decisions or process of the assembly – “the pueblo always has the final word.”

Underlying these principles are the three founding principles of the EZLN: discipline, companionship, and unity. It seems to me that they have rejected a unity that erases difference and hides oppression and demonstrated a new form of unity: a commitment between thousands to be companions in a life-long struggle for “a world where many worlds fit.”

With gratitude and tears we left the community and returned to the caracol for the Q&A session and closing celebration. A common question among students was, “How can we support you? How can we join the movement?” Our teachers made their expectations clear, saying that we should not aim to help their struggle or to adopt the Zapatista way of life. Instead, we can ask ourselves, “What could autonomy look like in each of our own corners of the earth? What are our principles of organizing and how do we live them with discipline and celebration?” And we can build a new way of life according to our own histories and needs, according to the collective decisions of those who have the dignity to rebel.

All photos were taken by two fellow alumni who were with me in the caracol and the autonomous community. Their media collective “Sónika en Sintonía” is based in Bogotá, Colombia.